image

image

Punishment follows crime

Oral traditions in India are full of stories of hell and the terrible punishments that await the wrong-doers after death. When these basically moral lessons are found evocatively portrayed in printed versions, they throw startling insights into a peoples imagery and thoughts , finds Ranjita Biswas

Ravana abducted Sita, another’s wife, thus committing a crime, and so he was punished by death in the battle field. The Kurus were unfair to the Pandavas; many a time they tried to get rid of their cousins who stuck to the right path and ultimately had to pay the price. Besides in the epics which were actually oral stories with moral message handed down from generation to generation, the folk tales also carry the message- crime does not pay.

In the moral fabric a society or community builds up, crime and punishment have been essential ingredients ‘to teach’ as how to be good, upright citizens- or else, rot in hell! To make the message clearer, even better is to graphically illustrate what can happen to the person in the nether world – what kind of punishment awaits for what kind of crime to put the fear of God- literally, in the living beings.

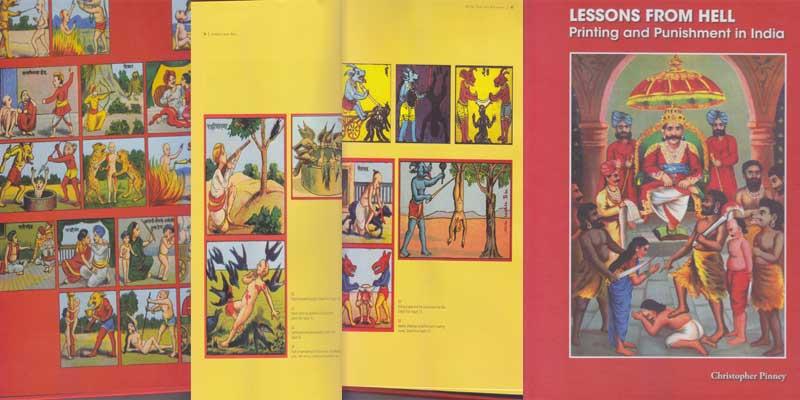

Lessons from Hell: Printing and Punishment in India (Marg) by Christopher Pinney is a remarkable book that amply proves that point. The author, a professor of anthropology and visual culture of London, is deeply interested in print culture and photography in South Asia and popular Hinduism in central India. This leads him to explore the world of printed images of ‘Hell’ figuring in popular imagination during the 19th and 20th century India.

What attracted him to the subject in the first place? “Seeing the prints in use in rural Madhya Pradesh, pinned to walls, sometimes framed, and seeing how often villagers referred to them. I was struck by how [they] were continually revised as part of the changing ‘history of hell’,” he says.

The images, in the fashion of calendar art, are often lurid, over-the board, even voyeuristic, one feels. Pinney agrees: “They are startling because of the violence and nudity. I was struck from the beginning by the ambivalence of using such lascivious images to enforce an austere morality.”

For example, women images are often in the nude (for not listening to the husband or running away with a paramour, etc.) while men are shown facing blood-curdling punishment at the hand of the demons at the court of Yama, the god of death.

There are also many other illustrations of karni-bharni –‘reap as you sow’ which show how cruelties committed in lifetime are met with the same fate after death. For instance, a man who overloads a cart drawn by bullocks himself becomes a beast of burden whipped mercilessly in hell; a man who shoots birds gets pecked by birds; a betrayer’s eyes are blinded by venom of a snake, so on and so forth.

The concept of crime and punishment to thwart moral aberration is , however, not uncommon in communities and religious discourses across the world . So these images could be a part of the ‘connected histories’, one would assume. But Pinney disagrees, “Humans seem to be able to independently arrive at pictures of hell that have a lot in common but also remain the product of distinct traditions.”

Questions still arise as to why did the 1880s see a proliferation of these graphic illustrations of an essentially oral tradition? Could it be due to the Victorian mores under the British colonial time or the availability of easy printing, or both?

Pinney feels that Victorian morals may have been a factor, but in general this is imagery that appeals to mofussil and subaltern consumers. It’s not chiefly the product of a bhadralok transculturation. The imagery (its landscapes and moral tropes) are those of the small town where the rural and the urban meet.

More likely is that these images are “the product of a fusion between enduring puranic classifications, the grid-like structures of moral teaching games like ‘gyan chauper’, and an iconography of retribution that is established in Jain manuscript practices. The booming print culture of the 1880s is the key: it is this modern technology that hugely amplifies what may otherwise seem merely ‘archaic’.”

Lithography reached India in the 1820s from the West. Cheap, easily portable and relatively easy to produce, it caught the fancy of the public and printers alike. The Calcutta School of Art produced some vibrant images in the early stages bringing nearer the images people knew as moral lessons discoursed orally for generations. Then graduates from the government art college founded the Calcutta Art Studio in 1878. The Chor Bagan and Kansari Para presses produced prints in vibrant images that the public lapped up. This was also when Pune-based Chirashala Press also started printing somewhat similar images.

One thing, however, seems puzzling. Considering the predominance of moral lessons Hinduism invokes emphasizing good deeds and the aspiration to reach ‘Heaven’ thereof, there are very few prints depicting the ideal after-death world compared to the overwhelming portraits of the evil hell with all its fearful images.

“It’s very striking,” Pinney agrees. “ [Indeed] moksha is essentially a void, one that is necessarily un-picturable, an escape from the burden of representation.” But the more interesting fact is the broader issue of the human embrace of negativity. “Why do we love disaster movies? Why is ‘bad’ news always ‘better’ news? Why are these prints so fascinating? We are Homo apocalypticus.”

Top Headlines

-

Art and Culture

Rich tribute to Bhupen Hazarika at Kolkata Book Fair marks birth centenary

January 29, 2026

-

Art and Culture

Kolkata Vistiwalas: The Last Bearers of Water

January 16, 2026

-

Art and Culture

Beyond Old and New: Bickram Ghosh and the Art of Fusion at Serendipity

December 25, 2025

-

Art and Culture

Saptak Music School of Pittsburgh hosts spellbinding evening of Indian classical music

September 23, 2025

-

Art and Culture

Zigzag to clarity: Sonal Mansinghs dance of life captivates Delhi

September 08, 2025

-

Art and Culture

USA: Santoor Ashram Kolkata mesmerises Los Angeles with a celebration of Indian classical music

August 27, 2025

-

Art and Culture

'Feels like a tonic in my musical pursuits': Flute virtuoso Pandit Ronu Majumdar receives Padma Shri

June 06, 2025

-

Art and Culture

Of Paris, a chronic pain and a pivotal friendship: Frida Kahlo meets Mary Reynolds at the Art Institute of Chicago

April 16, 2025

-

Art and Culture

Prabha Khaitan Foundation celebrates 'Vasant Utsav' at Indian Museum Kolkata

March 15, 2025

-

Art and Culture

Musical concert 'Ami Bhalobashi Bangla Ke' to be held in Kolkata on April 19

February 20, 2025