IMAGE

IMAGE

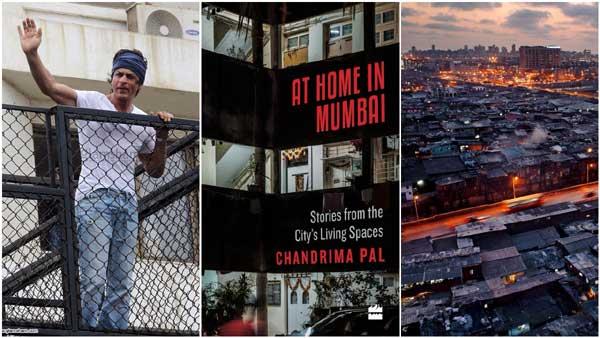

At home in the Maximum City

Filmmaker Basu Chatterjee in 1972 made Piya Ka Ghar. The Jaya Bhaduri-Anil Dhawan starrer was the story of a reality check for a newly wed couple desperate for their moments of privacy as they live in a cramped room in a Mumbai chawl with the entire family. Journalist and writer Chandrima Pal's new book A Home in Mumbai (Harper Collins) is inspired by the never ending search of Mumbaikars- be it Shah Rukh Khan or a commoner- for a living space they can call a home in the Maximum City

The second is a dream shared by all the people who have landed here from all over the world. In Maximum City, Suketu Mehta writes about how scarcity of land is what shapes the city’s culture, philosophy, politics and economy. That and the cumulative energy of the homeless who have been braving the struggle and the dystopian living conditions in the hope of a better future and more than a toehold.

In 1977, Gulzar wrote Gharonda, a film starring Amol Palekar and Zarina Wahab that captured the essence of the Bombay mirage. Palekar and Wahab are your regular middle-class working couple, who dream of getting married and moving into a small flat of their own. They share their respective homes with flatmates and family and work hard to build a corpus for their ideal home. Unfortunately, the builder turns out to be a con man and the young couple’s dreams of starting a new life in a new home comes to a bitter end, and so does their relationship.

Basu Chatterjee, one of the pioneers of Hindi new-wave cinema, made a film called Piya Ka Ghar, starring Jaya Bhaduri and Anil Dhawan. It was the story of a young girl from a village who gets married to young man in a large family living in a cramped room in a Mumbai chawl. While grappling with the lack of privacy, space and the peculiar dynamics of the family, she comes to terms with how the ‘city does not have enough place for everyone in its homes but there is always enough place for everyone in its heart’. That was in 1972.

Not much has changed since the film was made.

In 2014, while covering the Maharashtra assembly elections in Mumbai, veteran journalist Shekhar Gupta wrote an article titled ‘Mere Pass Space Hai’! He said: ‘No other city is perhaps as obsessed with the idea of space as Mumbai. ... It defines its people, its culture and its conversations. It defines what they do, what they are pushed to do and what they are unable to achieve.’

.jpg)

Excerpts:

A house for Bollywood stars is more than just an address. It is a trophy they like to gift themselves. A reward more powerful and satisfying than any of the statuettes that the award functions dole out every year. A trophy that tells the world that the star has arrived.

CITY OF STARS

It was the day before the release of his most unabashedly commercial film. Shah Rukh Khan, in his inimitable style, had thrown open the doors of his palatial bungalow to hundreds of media persons, friends and colleagues. It was a grand Iftar party and a toast to the success of the film – a foregone conclusion at that time. There was a lavish spread on long tables – kebabs that melt in the mouth, rich, layered biryani, fresh dahi vadas and an array of desserts. Outside the high walls, a sea of people had gathered, the tide swelling every minute. Men, women, star-struck rookies, veteran writers, producers, distributors, close friends and his trusted PR aides buzzed around the split-level, Victorian lawns, eyes trained on the grand stairway.

.jpg)

Well into the party, he appeared. Pausing at the door on the upper level overlooking the lawn. Dressed in a black kurta and salwar contoured for his incredibly sculpted body, a pair of dark aviators, he paused dramatically, waving out to his ‘guests’ who dropped whatever they were doing to reach out for their cameras, microphones, to get the moment evidently planned to heighten the drama – the dark knight against the pristine, venetian backdrop of the white building. ‘Shah Rukh’ ‘Khan Sahab’ the voices urged, as the star slowly walked down the winding stairway, pausing, blowing kisses, waving, smiling and then finally stepping into the lawn greeting, hugging every one. Seasoned journalists were reduced to giddy-headed teens in his presence, as he gave each one what they would say was a ‘moment’ – a hug, a smile, a few words, an ‘exclusive’ sound byte.

In a few minutes, there was a fresh ripple at the durbar. The star’s family – his wife Gauri, and his two children (Abram was not in the picture yet) and his sister had made an appearance. He joined them on the stairs, pausing at every turn of the picturesque setting for photo ops – each member of the family handling the hundreds of cameras with the ease of one to the manor born. And when the star climbed on to the platform next to the high walls, into a caged enclosure to wave out to his fans, with his daughter Suhana by his side, the crowd erupted in joy. From the other side of the wall, it seemed as though Sachin Tendulkar had hit a winning sixer. A moment that was recreated in his critically acclaimed film Fan.

A young journalist, in his early twenties, looked at the slim silhouette that looked so much larger than life on the screen, and now against the blue Bandra sky, nodded his head and murmured. ‘Isn’t it amazing how this middle-class boy with no connections or money arrives in the city and creates an asset that is a destination in itself? An outsider who has left his unique stamp on Maximum City?’

It was hyperbole but true. Just like the city.

I recalled an earlier interview that the star had given to a news magazine. He had said: ‘People will always remember me for Mannat. It belittles my other achievements but it’s okay. Beyond your house, whatever you get is value addition. As they say, you’re not going to eat money and the food won’t taste better if you eat from a silver plate.’

FINE LINES

It was a pleasant December day in 1992, almost a decade after the textile mill strike fronted by Dutta Samant seeded the first germs of rot in the heart of the working-class ecology of the city. The residents of Natunchi Chawl had gathered around a large television set one morning. Some of them had subscribed to Newstrack, India’s first video news magazine, produced and anchored by Madhu Trehan. This particular edition was special.

‘Jai Sri Ram’, jubilant men thundered. Young boys ran around cheering for friends and jeering at imaginary enemies. It was all in jest. Some jolly good fun. Something to talk about and make games around. Until, of course, the milkman called that fateful morning and everything changed.

‘The Muslims have poisoned the milk. They want to kill our children,’ he said.

‘I get goose bumps even today,’ says Swaroop, recalling that phone call, rubbing his fingers on his bare forearms. The whole game of demolishing enemies had suddenly turned real. It was a game that adults were playing and it was not funny at all.

The chawl, which was close to Bhendi Bazaar, the Muslim hub of the city, was on the edge and armed. When the riots did break out, male members formed groups to keep vigil all night. Cadres of the most influential political party taught young boys how to make petrol bombs. Weapons were fashioned out of playthings and kitchen stuff – stumps, knives and bats. Some even brandished scythes.

Every now and then there would be rumours. ‘Five thousand Muslims are headed this way, be prepared.’ Luckily, none of the weapons had to be used at Natunchi Chawl. ‘It was mostly rumour-mongering,’ insists Swaroop.

But there was damage.

.jpg)

Something changed in the city after the riots. Something in the air, in the sands of the Chowpatty, the iconic city beach, in the dark tidal waters of the Mahim creek. ‘There is too much mistrust, too much labelling, too much fear in all of us,’ says Swaroop.

‘The chawl was a symbol of peaceful coexistence, it reflected the old character of the city,’ he says. ‘All the bread that I sell here is supplied by Muslim bakeries. South Bombay does not have any shopping malls. We all go to Crawford Market, which is run mostly by Muslims. People from all over the city come to buy kites from Dongri, and fly it for Makar Sankranti. How can we live without each other?’

Swaroop’s six-year-old son Ishaan is a fan of Bollywood actor Akshay Kumar. The family was watching a film, Holiday, in which the star goes around killing terrorists. Ishan burst out, ‘Look at those terrorists he is killing. They must be Muslims.’ A shocked Swaroop asked his son where he had picked it up from. ‘Everyone says Muslims are terrorists,’ the boy replied. It took Swaroop a while to convince him otherwise.

Back at the Chill Mar, the world outside Swaroop’s food joint has got busier. One of the senior craftsmen in his team steps in to have a chat with us. He is from Kolkata. Artisans from Bengal are highly prized for their skills in gem and diamond setting. He is one of them and has been working here for fifteen years, commuting from distant Virar to Girgaon every day. Swaroop steps out to have a word with a young woman, possibly on her way home. Introductions are short and swift.

‘In a chawl close by,’ she points to another similar building around the corner, speaking in the easy, sonorous Mumbai English.

‘Do you like it there?’ I ask, suddenly aware of how shallow I sounded.

‘I love it ... wouldn’t trade it for anything in the world.’

She disappeared in the crowd returning from workplaces, pausing to pick up supplies, flowers and fruits.

I look around. In the darkening hour of the day, two young boys were playing cricket in the corridor of the chawl, women leaned over to exchange gossip and goodies, clothes were hung out to dry, and fragrant tulsi plants thrived in cement planters. Everything seemed just the way it used to be. Only the boys playing corridor cricket may soon demand an attached bathroom, a bride and a bedroom, perhaps in that order

Top Headlines

-

Lifestyle

Kolkata: Rotary honours Padmashri 2026 awardee Pandit Tarun Bhattacharya

February 17, 2026

-

Lifestyle

Can Sound Heal You? The Ancient Therapys Modern Comeback

February 17, 2026

-

Lifestyle

ACM India unveils National AI Olympiad 2026 to spot school talent for global AI stage

December 21, 2025

-

Lifestyle

'Dont join politics': Why Tharoor defied his mother and endorsed his conviction

December 15, 2025

-

Lifestyle

Birbhum: Sitaramdas Omkarnath Chair at Biswa Bangla Biswavidyalay

December 04, 2025

-

Lifestyle

Rediscovering Arunachal's Monpa Cuisine: One Womans Millet Momo Revolution

November 24, 2025

-

Lifestyle

Shiny things by Jinia: A luxury evolution by visionary entrepreneur, healer

November 19, 2025

-

Lifestyle

Mystique and Memories: Wiccan Brigade hosts its first Halloween Fest in Kolkata

November 17, 2025

-

Lifestyle

Rotary Club of Calcutta Samaritans hosts three-day youth leadership awards program for tribal students in Bakura

November 15, 2025

-

Lifestyle

Rotary Club, South Kolkata Vision inaugurate newly developed children's park in Sonarpur

November 15, 2025